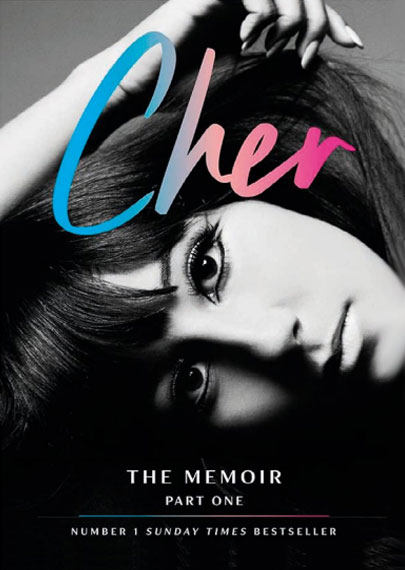

CHER: The Memoir, Part One

by Cher (HarperCollins, £25)

Gripping, honest and funny, Cher’s memoir (dedicated to her beloved mother Georgia) hurtles along at breakneck speed, covering her erratic early life and the ups and downs of her career. Her Armenian father, John Sarkisian, a slickly handsome heroin addict, gambled away his truck business before abandoning the family. Struggling to survive, Georgia, a stunning beauty with a powerful voice, left Cher (born Cheryl) in a children’s home run by harsh nuns, paying for her keep with earnings from singing in all-night diners and as a film extra.

A self-confessed ‘smartass’ teenager, Cher secretly borrowed her mother’s car and ran wild in Los Angeles. She was just 15 when 25-year-old Warren Beatty first kissed her. Some of the book is dark, particularly Georgia’s constant lack of awareness about men – she was married five times before Cher was 16 and seven times in total (twice to John). Each new man resulted in a new school, new friends and a new neighbourhood for her daughter.

Although ‘ballsy’ and determined, Cher also attracted manipulative men. She met her first husband, the singer Sonny Bono, aged 16, after applying to work as his cleaner – and was ‘dazzled’ by him. At the time Bono was an assistant to the record producer Phil Spector, and Cher ended up singing backing vocals for The Ronettes. The eccentric couple came to London after Mick Jagger suggested that Swinging London would ‘dig them’.

He was right: their 1965 single I Got You Babewas an immediate hit, knocking the Beatles off the top of the UK charts. The couple landed their own television show and seemed a picture of hippie bliss, but Cher remembers Bono as a ‘controlling’ man who insisted she wear ‘buttoned up clothes’.

Unsettling in places, there’s never a dull moment in this celebrity-strewn gem of a memoir.

Rebecca Wallersteiner