I was a Moonie – and have no regrets

The dress code for my 40th birthday party (raucous with jukebox, strobe lighting, lots of air guitar) was ‘1974’. People wondered why. I told them that 1974 was the craziest, happiest, scariest and, ultimately, the most life-changing year of my life – and I wanted my friends to reflect that by coming just as they were at the time.

Then I realised that it was going to be hard choosing my own outfit because at the beginning of that year, I had long hair and wore tatty T-shirts and jeans cropped just above the knee, but by the end I was cleancut in sober trousers and traditional shirt and collar.

The reason? I had met and joined the Unification Church, better known as the Moonies, whose leader, Sun Myung Moon, died last week aged 92. I had been travelling in America as part of my gap year and fetched up in Boulder, Colorado, where the movement ran a community centre on the outskirts of town.

There must have been at least 10 different nationalities at the centre, all getting along famously, and I was intrigued to find out why.

After hearing their teachings and experiencing a genuine warmth and sense of purpose, I felt as if I had found what I was looking for – not just an escapist alternative to a 9-to-5 existence and not just a new set of beliefs, but the chance to create a whole new way of living.

Mark Palmer in the 1970s at a Moonies event

Mark Palmer in the 1970s at a Moonies event

Hopelessly naive, I know. But that’s what comes with being 19 years old at a buzzy, high-spirited time when new religious movements (or ‘wicked cults’, according to your preference) were all the rage.

A little background: the Unification Church began in North Korea in the 1940s, although it was officially founded in Seoul, South Korea in 1954. Its teachings are a synthesis of shamanism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism and Christianity. The reason mainstream Christianity is incensed by Moon’s so-called Divine Principle is because it does not recognise Jesus Christ as the ultimate saviour.

Moonies believe that Christ failed in his mission to become the ‘Second Adam’ because he was crucified before he was able to marry and have children. A new messiah – the Lord of the Second Advent – was needed to complete Christ’s work on Earth and establish the Kingdom of Heaven.

But Moon himself was married several times and, even when he found someone that he regarded as the True Mother, it did not prevent him from producing children burdened by the usual trappings of imperfection. One son died on a plane after years of drug abuse, another committed suicide, and other Moon children currently are at loggerheads with each other, with more hostilities set to flare up now that their father is no longer around.

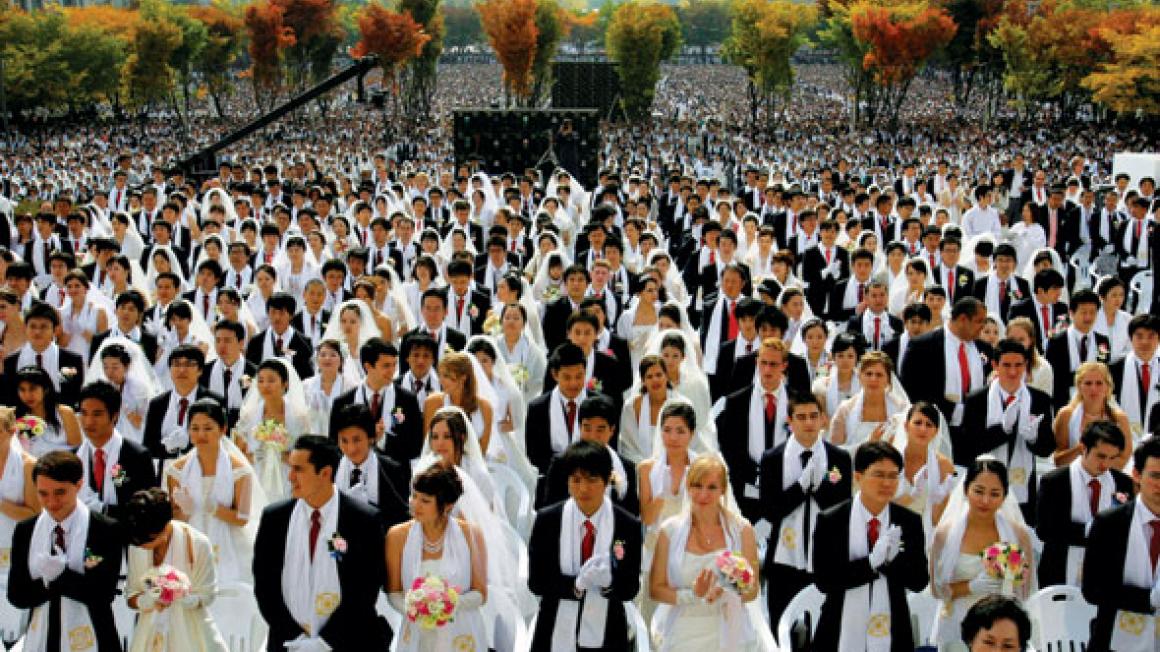

I left the organisation after about six years but during that time I did put myself forward to be married in a mass wedding ceremony, and my wife and I went on to have two wonderful children, although the marriage did not survive.

Those children are reason enough for me to say that I have no regrets about my involvement in the Unification Church (apart from causing my parents a lot of anxiety). But there are other reasons, too.

Rebellion is still alive today but it’s angry rebellion. Somehow – 40 years ago – many of us who were disaffected by the Vietnam War and fired up by music, soft drugs and the loosening of sexual mores, looked for a gentler, more spiritual alternative.

And, frankly, I’m pleased that I experienced some sort of religious life. It may have led to a dead-end street with the Moonies, but it opened up new avenues of exploration that have remained with me ever since.

Never mind the behaviour of Moon and his senior lieutenants, there were some special people further down in the organisation. They were in it for the right motives. I like to think I was in it for the right motives.

Certainly, it wasn’t a comfortable existence. We seldom slept in beds; we fasted; we sometimes spent whole nights in prayer. And we received no remuneration.

I don’t resent any of that. In fact, the whole thing left me strangely enriched. I learnt a lot about the importance of self-discipline and about working with a group of disparate people. I had an opportunity to study The Bible. I made good friends too, although only one still has any connection with the Unification Church.

People who know about my Moonie years sometimes ask how hard it was to leave once my disenchantment had gone beyond the point of no return. Very hard is the answer. I often remember thinking how the truth was meant to set you free, and yet I had found this ‘truth’ that trapped me in it.

Then I came across a Church of England priest who, rather than persuade me of the errors of my religious ways, suggested I read a book, The Christian Agnostic, by a Methodist minister called Leslie Weatherhead, a controversial figure who died in 1976. Weatherhead once said that creeds and confessions of faith were ‘museum specimens’. He didn’t believe in the virgin birth either.

Weatherhead wasn’t afraid to doubt, whereas Moon inhabited a world where doubt was seen as weakness. Moon thought he had all the answers and that was one of the things that destroyed his own humanity.

Mind you, I’m sure I could have come to these same conclusions in a less extreme way. Certainly I would never advise anyone to do what I did – which is different from regretting the whole escapade

Oh, and in the end I opted for the frayed jeans and tatty T-shirt for my 40th birthday bash.