Book Reviews: 27 January

OUT NOW

THE KEEPER OF LOST THINGS by Ruth Hogan (Two Roads, £16.99)

THE KEEPER OF LOST THINGS by Ruth Hogan (Two Roads, £16.99) The back stories, real or imagined, of lost-and- found objects form the centrepiece of this exquisite, absorbing novel, a potent cocktail of insightful psychological realism, whimsy and glittering magic, where hopes and new beginnings glint off the sharp edges of grief and loss. It grabs you right from its intriguing opening scene: ‘Charles Bramwell Brockley was travelling alone and without a ticket on the 14:42’… inside a Huntley & Palmers biscuit tin. Who or what is he? The ashes of a dead man, as it turns out.

Anthony is an ageing writer who obsessively collects and catalogues found objects – the aforementioned ashes; a piece from a jigsaw puzzle; a dark blue button – in a lifetime’s bid to atone for a broken promise. As he approaches death, he bequeaths this bizarre collection to Laura, his devoted assistant and friend. She too has been lost and found: after escaping a soul-destroying marriage, her life was transformed by answering an advert in The Lady. Their stories intertwine with those of a vibrant and varied cast of characters, including another woman who, decades earlier, had also taken a life- changing step through the pages of this magazine.

Hogan’s prose is considered, expressive and vivid, but never overwritten. Her characters reveal themselves gradually, much as the found objects acquire layers of meaning as we become acquainted with their provenance and history. A charming read that seems bound to become a book club favourite.

Juanita Coulson

SHORT SENTENCE by Jessica Berens (Grosvenor House Publishing, £9.99)

SHORT SENTENCE by Jessica Berens (Grosvenor House Publishing, £9.99)Jessica Berens spent three years working as writer-in-residence at HMP Dartmoor, ‘a cross between Gormenghast and an Escher drawing’, where 600 men are imprisoned for ‘drugs, violence, aggravated burglary, incidents involving weapons, beating up the missus, beating up a random stranger, murder’. Her remit was to support arts activities.

Berens writes beautifully. She describes life on the wings in illuminating detail: ‘Food [was] a constant source of morbid fascination… as was the perceived filth, dishonesty and incompetence of the kitchen.’ Clothes are issued from a stock that includes a heap of communal underpants. Once a day the inmates ‘walked around the prison as a wave’.

This chronicle wryly describes an institution where banality and craziness knock up against the daily threat of violence and a lurking horror – many of these men are perpetrators of crimes against children. With little more than the help of a staple gun, Berens encourages her students to express themselves in creative writing classes, helps them to form a rock band and produces several issues of Tor views, the prison magazine. A compelling read – bleak, wildly funny, anarchic at times, but underpinned by considered and serious comment on the current state of the criminal justice system in this country.

Louise Guinness

BOOK OF THE WEEK

A bloom of meanings

A bloom of meaningsDAFFODIL: Biography Of A Flower by Helen O’Neill (HarperCollins, £18.99)

O’Neill was inspired to document the daffodil’s story while recovering from cancer, after receiving messages of hope symbolised by the flower. She holds it in high esteem: ‘The daffodil has threaded its way through much of human history and within its story lies our own,’ she writes. This radiant bloom has embodied symbolic meanings such as death, spring and the afterlife, implanting itself into every cultural sphere from psychology and poetry to popular culture.

Billed as a biography, the book includes an array of historical information charting the flower’s early, resplendent glory days to near-extinction and back again. We are told it first appeared between 29 and 18 million years ago, how ancient cultures feared it for its high toxicity, and how some saw the flower as a living link to the hereafter. Roman soldiers carried daffodil bulbs as suicide pills in case of capture, but that didn’t stop its cultivation as a herbal medicine during the Middle Ages. The Scottish horticulturist Peter Barr, universally known as the Daffodil King, who ultimately saved it from extinction, is also duly noted.

Penned with passion and commitment, this endearing study will enrapture a wide audience. Including stunning botanical plates, paintings and a comprehensive daffodil classification guide, it is a rare treat.

Elizabeth Fitzherbert

COFFEE TABLE BOOK

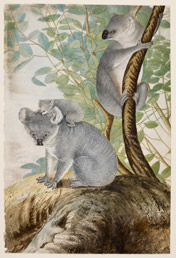

THE PAPER ZOO: 500 Years Of Animals In Art by Charlotte Sleigh (British Library, £25)This survey of zoological illustration is as much a history as a cabinet of curiosities. All of animal life is here, as documented through the eyes and cultural perspectives of travellers, naturalists, academics, artists and amateurs. There are classics of the genre, like Audubon’s birds and Merian’s insects, but sleigh also unearths lesser-known and often intriguing works.

Koalas, watercolour by John Lewin (1804)

Koalas, watercolour by John Lewin (1804)JC

PAPERBACKS

SHTUM by Jem Lester (Orion, £7.99)Based on Lester’s own experiences, Shtum is the story of autistic 10-year-old Jonah, whose world of order and silence is threatened by members of his family. Separations and heartbreak ensue and Jonah moves in with his father and grandfather, into a claustrophobic house in north London. Through Jonah’s naivety and joy in life, the three generations of men learn about their own shortcomings, the importance of family and the enduring power of love. Lester’s unusual book conveys a profound message about the whole spectrum of humanity, focusing especially on male familial relationships. While the format and use of illustration takes a while to get used to, it is worth sticking with for a thought-provoking and moving read. Helena Gumley-Mason

SUMMER BEFORE THE DARK by Volker Weidermann, translated by Carol Brown Janeway (Pushkin Press, £8.99)

As the storm clouds of fascism and war gather in 1930s Europe, the Austrian literary luminaries Stefan Zweig and Joseph Roth seek refuge in the Belgian seaside town of Ostend, where they reignite their estranged friendship. Weidermann has drawn on letters, diaries and archives to tell their melancholy story. He evokes a lost world of promenades and parasols, bistros and casinos, ‘where the gaily coloured bathing huts glow in the sun’. Trapped in this holiday limbo, writers, artists and their lovers congregate at the Café Flore to watch the sun go down as Europe begins to crumble into chaos. Although frustratingly short, Summer Before The dark is a mesmerising, haunting read. Rebecca Wallersteiner