Learning the ropes

Just like Mrs S, I too had been attracted by the lovely sound church bells make. One Christmas holiday I was at a loose end. Seeing a notice in the post office about an open day at the local church tower, I decided to investigate. I was encouraged to ring some hand bells and soon gravitated to the real thing.

It seems that only in the UK do church bells ring to a kind of mathematical formula, whose origins lie in the 16th century. In the tower where I ring, there are eight bells ranging from the lightest, the treble, to the heaviest, the tenor. Being female, I ring any of the five lightest bells, leaving the heaviest for the men.

Even without doing any actual ringing, there are certain lures – the atmosphere of an ancient church built of stone and silence, the spiral staircase that precedes the ringing chamber, the – dare I say it – slightly Dad’s Army atmosphere. It all seems to belong to another era, where the iPod and the BlackBerry hold no sway.

The first job of any session is to ‘ring the bells up’. In the belfry, the downward-facing bells have to be raised to a vertical starting position. I used to try and avoid this job by arriving five or 10 minutes late and hoping someone else might have done it first. Pulling up the tenor bell is hard graft – it may sound sexist, but it is generally a man’s job – you need strong arm and leg muscles to keep the rope taut and maintain contact with the bell as you bend down and stretch up.

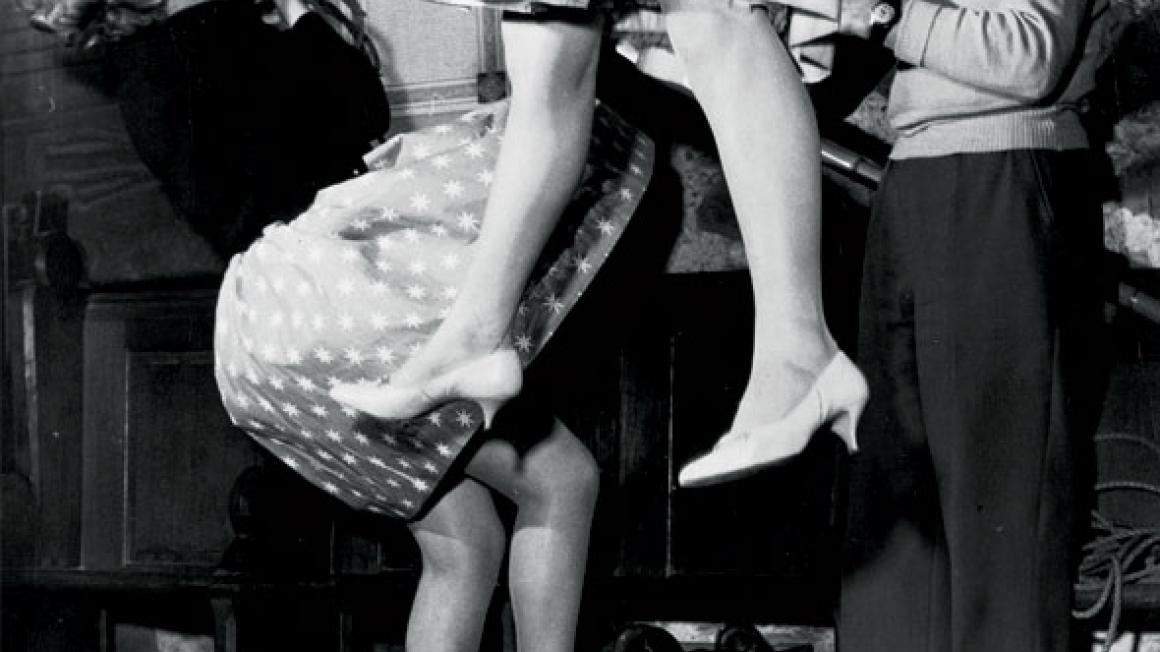

This upward/downward movement gives rise to what I call the ‘midriff problem’. Monks definitely had the right idea here, as a long habit is the ideal garment to avoid any possible chance of stomach sightings.

Once the bells are up, the tower captain assigns everybody to a particular bell and we practise rounds (a bit like piano scales) and call-changes. If you’re elected to ring the treble, you call out the starting order: ‘Look to! Treble’s going! She’s gone!’, which gets everyone’s attention.

Bell-ringing is an exact art and you are constantly looking at other ringers to make sure you ring your bell at precisely the right time. Eye contact and concentration are very important – daydream for a second and you lose the rhythm. Once the warm-up is over, it’s on to sequences of ringing patterns with beautiful titles like ‘Plain Bob Triples’ or ‘Steadmans’. These are for the die-hards, so I perch in the window to listen and learn.

Finally, as the session draws to a close, we have to ‘ring the bells down’. Even now, I still find this hard to master. Ringing down needs a lighter touch so that the bell swings faster and faster, the rope in your hands gets longer and longer, and with great manual dexterity you’re supposed to twist the rope into neat coils. Normally, novices end up with one huge coil that flaps about, and in my case hits me repeatedly on the forehead. Perhaps this is where Mrs Springthorpe came unstuck.

Ringing down also brings out my competitive instinct. ‘If it were a race, you would have won it!’ says the tower captain to me cheerily. I take it as a compliment.

Bell-ringing, just as the Reverend Paul Burden (where campanologist Mrs Springthorpe rings) said, is indeed ‘a very skilled hobby’.

For more details, visit Discover Bell Ringing: www.bellringing.org or enquire at your local church or diocese office.