My friend the spy & why we're all pretty silly about art

‘I hope you like coffee,’ he prefaces the story. ‘I intensely dislike tea.’

He pours us both a cup from a cafetière, offers a chocolate biscuit and begins. ‘Ages ago, perhaps as far back as the late 1960s, I found a funny picture in Christie’s. It was in a pretty dire state – but I recognised it as an early Hogarth.

‘I got it for nothing, took it home and repainted it, making it look much better than it was. I then sent it back to Christie’s and the Tate bought it.

‘For a few years, it was the earliest Hogarth in the Tate… until some Hogarth scholars came along and it was demoted. I haven’t seen it for years, but I was jolly chuffed when they bought it.’

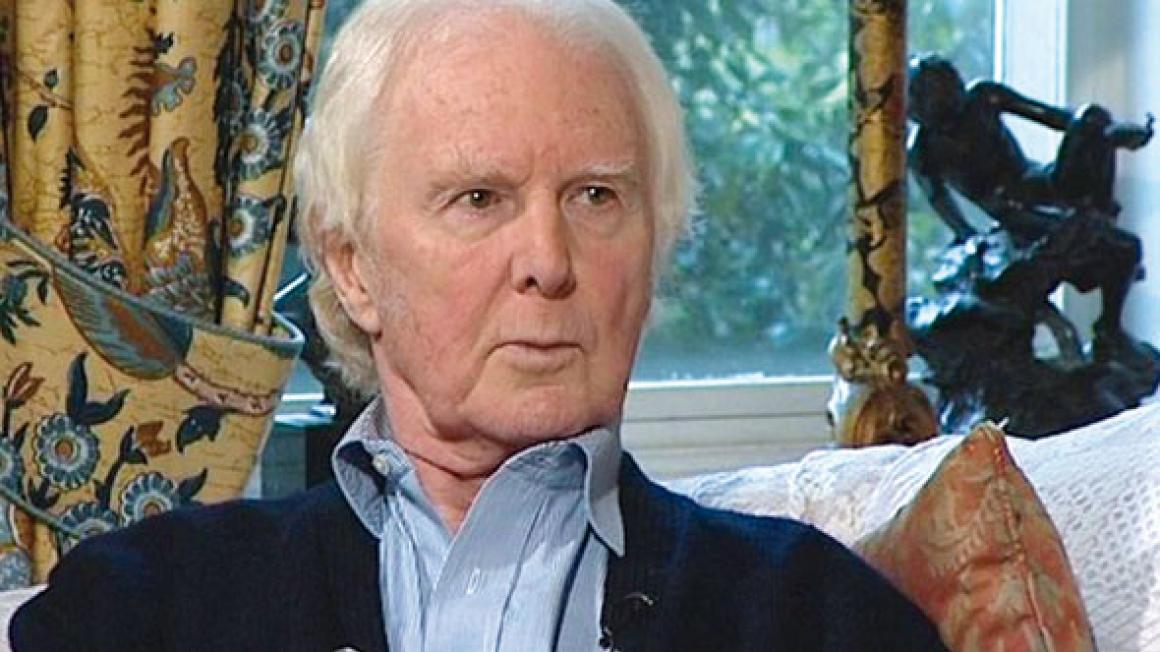

The story is typical Sewell: surprising, bold, and more than a little mischievous. Furthermore, it is proof that he is an art critic who can also handle a brush.

Sewell was born in 1931. His father, Peter Warlock, was a minor composer and ‘waspish maker of enemies’, who instructed Sewell’s mother to have an abortion when she became pregnant during their brief affair. She refused – and Warlock killed himself before Sewell was born.

Brought up poor by his mother (a background belied by his exquisitely tuned, upstairs accent), he went on to study at the Courtauld Institute of Art. He started work at the auction house Christie’s, before earning his place as Britain’s foremost – and most formidable – art critic, currently for the London Evening Standard.

It certainly has been a life less ordinary. Posing naked for a voyeuristic Salvador Dalí (Dalí pretended he was taking photographs, but there was no film in the camera). His friendship and defence of the Cambridge spy ring’s fourth man, Anthony Blunt. His epic sexual adventures. His spats with and skewerings of the lickspittles and windbags he so evidently despises.

Sewell is 82 now, but despite a weak heart and creaking joints – ‘my back is crumbling’ – he remains surprisingly boyish. And his Byronic good looks prevail. But age is taking its toll. Once a keen skier, mountaineer and tennis player, his movements are now slow and painful.

‘What am I left with?’ he asks waspishly. ‘Wandering around the garden with a pair of secateurs?’

In fact, these days, death is often on his mind. ‘I had rather a bad day yesterday, which happens from time to time,’ he tells me. ‘My heart problem, which is quite serious, sometimes kicks in. I went to bed about 3pm but woke in the middle of the night and just lay there thinking about death, how easy it would be to die in the early hours of this morning.

‘I don’t want to fight it when it comes.’

In fact, just last year Sewell wrote about his plans to commit suicide on a park bench, full of gin and pills. He called it a ‘great comfort’. So has anything changed?

‘When I wrote about suicide, I had a lot of letters and they all said “don’t do the easy thing and take all the pills, as the chances are they won’t kill you and someone will rescue you and you will be worse off”. I got several letters from doctors, too, and they said the only way to do this is to go to Dignitas [a flight away in Switzerland].

‘But the thought of Heathrow being the antecham- ber to my death…’ he groans theatrically. ‘Heathrow is my idea of Hell.’

For a man who has spent his life writing about art and beauty, Sewell is surprisingly nihilistic. He certainly doesn’t have much time for God. Despite once considering the priesthood, he is now agnostic. ‘When I was a tiny child, I hated that hymn ‘God be in my head and in my understanding’. The idea of God being in my head! At that age I didn’t know about anything, but the idea of that? Arghhh.

‘There’s a very eff ective anti-God response at the moment,’ he adds. ‘Where is God in the Somerset levels? It’s not nearly as serious as a tsunami or an earthquake, but the fl ood has probably killed every badger in the county.’

But what if he did meet God at the Pearly Gates?

‘I’d say, “How could you? How could you, to begin with, make sexual pleasure so awkward, so diffi cult – and then plague us with it.”’

Even the prudish and the modest would struggle to talk about Sewell without mentioning his fl amboyant love life. In his memoirs, he tots up ‘a thousand casual lovers, one-night stands or furtive sexual encounters’, and he tells me about them with ‘abandon’, a favourite word of his. (He also spends a good while waxing lyrical over the posterior of Michelangelo’s David.)

But despite being homosexual, he has felt the pressure to settle down with a good woman. ‘It seemed expected,’ he says. ‘But then, I think, common sense came to the rescue. It would have been a disaster.

‘I still see one of the girls who was a possibility,’ he adds. ‘The awful thing is that I think she’s still in love with me. She married someone else and had lots of children, so every time she turns up I go through this distancing, trying never to be within reach.’

In fact, he confesses that this unrequited romance has been going on for nearly 60 years. ‘She knows,’ he adds. ‘She delivered an ultimatum, donkeys’ years ago, saying it’s now or never – and I remember saying that I had no inclination even to experiment.’

Art, of course, is his true love, an antidote to his inherent nihilism. ‘Nothing has any point. We make the point,’ he says. ‘You invent things to make life worth living.’

But he certainly doesn’t pull his punches and makes perfectly clear his contempt for the path much contemporary art has taken. ‘I think we’re all pretty silly about art,’ he explains. ‘Look at Florence in the early 15th century. Then, probably nine out of 10 people couldn’t read but they’d look at sculptures and frescoes and they’d understand them and what they represented.

‘You could look at the sculpture of Donatello in the early 15th century and the sculpture of Rodin in the late 19th century and they have the same aesthetic and the same illiterate people would have had the same response.

The Golden Calf by Damien Hirst

The Golden Calf by Damien Hirst‘But then we got into the 20th century and we developed other aesthetic criteria, so now art has become largely unintelligible to everybody – even those people who pretend to understand it. What is the point? What has been the point of making art virtually unintelligible to 90 per cent of the population?’

Certainly he can be an unabashed iconoclast. In his view, David Hockney’s recent work is ‘loud and shouty’, while Damien Hirst is ‘a maker of things, which foolish people are prepared to pay a lot of money for’. He is similarly dismissive of Richard Hamilton, the subject of a major new Tate Modern retrospective (although he does think that his painting The Citizen is one of the great works of the 20th century).

'This will be the last Hamilton exhibition I will have to see. It won’t give me any pleasure, none of the others have,’ he says. And these are mild judgements by his standards. He once bequeathed his eyes to the rival art critic Sarah Kent, and planned to send the leftover bits from his heart bypass surgery, preserved in formaldehyde, to Damien Hirst.

‘In the end, though, the bits were just a bit too small, and I felt abashed,’ he tells me. ‘So Damien never got his bits of me. It was well intentioned, though.’

He does confess to changing his mind about Charles Saatchi, though. He says that he used to dismiss Saatchi as a collector specialising merely in the ‘oddest, the most objectionable and the most vomit-inducing works’ to drive up visitor numbers to his galleries. In the past few years, however, he has ‘come to realise that everything I knew about immediately [sic] contemporary art, I knew not from the Tate, but from Saatchi. Saatchi showed us what was happening, now. Whereas, [Nicholas] Serota at the Tate – dignified, remote – showed us nothing but things that are well-known.

‘I don’t understand the Tate,’ he goes on. ‘They have that hugely expensive museum at Bankside with millions of people going through it and what do they see? I don’t think Serota is running it very well.’

It’s not just art and artists that are subjected to his ire. Politicians are another pet hate. ‘There are 65 million people in this country and the best we can throw up for those 650 places in the Commons is what we have there now. These. Are. The. Cream. Of. Our. World. How does this happen? Is this democracy? If so, I think I’d rather have a dictatorship.’

But there’s far more to Sewell than bluster and broadsides. He can also be fiercely loyal. Take his relationship with Anthony Blunt. Sewell studied under Blunt at the Courtauld Institute in the 1950s, when they became firm friends. In 1964, however, Blunt, who was also surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, confessed to being a Soviet spy.

At the time, MI 5 kept Blunt’s confession under wraps – until 1979, when Margaret Thatcher made his secret public. It was one of the great scandals of the day and Blunt was stripped of his knighthood and publicly ruined. Sewell, however, stuck by him, spiriting him away and playing a key role in helping Blunt to escape the media. But does he still sympathise with his friend, the spy who died in 1983? ‘I take a lawyer’s view of it,’ he replies. ‘There was a bargain and she [Thatcher] broke it. And I’m not sure it did much good to anyone. The further revelations just meant that a lot of broken old people suffered.

‘Anthony had turned the Courtauld Institute into the most prestigious, the most scholarly, the most disciplined institute of its kind in the world. And she spoilt that. The Courtauld was very damaged by it, because the people who succeeded Anthony did the most extraordinary back-pedalling. They tried to make themselves out to be good little boys and distanced themselves from everything he did. It was sickening.

‘I have no regrets playing the part that I did. I did exactly what Anthony asked me to do – to get him out and provide a diversion. It was a wretched time. We can be very cruel as a people. For taxi drivers not to pick him up and for bus drivers to kick him off…’

‘I’m a natural conservative, so communism has no appeal to me. But you had the terrible spread of fascism between the wars and communism must have seemed at least one means of opposition to that.

‘And what the Anthonys of the world didn’t realise was what was happening under the biggest communist regime of them all: how many people were being murdered,disenfranchised, sent off to the gulag.’

Sewell is certainly an attentive host – and generous with his biscuits – although he becomes strangely defensive when I ask him to sketch Lottie, his beloved and rather protective Staffordshire bull terrier.

In fact, while Sewell can paint ‘better than most painters’, he burnt many of his works before moving into his current home. Only a few remain, including an abstract painting dating back to his school days. ‘I was interested in Russian constructivism,’ he chuckles. ‘I occasionally stumble upon it when I’m looking for something else. It’s quite possibly the best thing I ever did’. He also tells me that being able to paint has certainly helped him as a critic, although being an artist would never have been a fulfilling profession. ‘The trouble was that I never had anything to say. Whenever I painted a picture, it was simply an image. I didn’t feel anything.’

It is a typically honest confession. But then it’s his honesty that makes Sewell so likeable, such good company. The pity is that he may soon step out of the limelight. ‘I don’t want to go on writing about art until my dying day,’ he reveals. ‘I’m repeating myself now.’

When that day comes, the world certainly will be a less colourful place. For while Sewell has made many distinguished enemies during his life’s adventures, I’ll wager they’ll all miss him when he’s gone.

Brian Sewell’s memoirs, Outsider (£25), Outsider II (£25) and Sleeping With Dogs (£12.50) are published by Quartet Books.

THE SCANDAL UPSTAIRS

In the past, Sewell has revealed how, in the 1950s, he was used as ‘sexual bait’ by Christie’s to help seal deals. ‘My friend Bruce Chatwin had the same thing,’ he tells me. ‘We compared notes. There is absolutely no doubt about it. When you’re staying overnight at a house and wake up at midnight and find his Lordship sitting at the end of the bed, there really is no doubt. We were sometimes sent to the same houses for the same reason.’

SEWELL’S MOST IMPORTANT LIFE LESSON

‘I was once having trouble with the idea of the transubstantiation of the host. My parish priest said: “My boy, you must bring everything to the bar of your own judgement.” I grew to understand what that means and I have been bringing things to the bar of my own judgement ever since. I don’t believe anything that anybody tells me.

‘There are people who you want to believe. My professor at the Courtauld, Johannes Wilde, one of the greatest art historians of the day, taught us about Michelangelo and said that the great gure of David was a high relief, not a sculpture in the round. But if you go to Florence and walk around it, which you can (awkwardly), you can see that it is anything but a high relief. This is a gure in the round, a gure Michelangelo really looked at. He had looked at a lot of boys’ bums before he sculpted that one. I had found a chink in Johannes’ armour. I was right and he was wrong.’