RETURN TO AKENFIELD

Akenfield was to become one of the best-known villages in England. But the place never existed. The stories are true, but Akenfield, written in 1969, is a fiction, a name coined by Ronald Blythe to represent the real villages he was writing about, Debach and Charsfield. Living in an old farmhouse at Debach and being churchwarden at St Peter’s in Charsfield, Ronald Blythe knew nearly everybody, farmworkers, schoolteachers, vet and blacksmith, rural dean and gravedigger. They all talked to him of village life, past and present, and they all called him Ronnie. People still do.

Peter Hall heard the music of Suffolk voices on that train. ‘I seemed to hear my grandfather talking,’ he wrote.

1. Garrow Shand as Old Tom and Lyn Brooks as Charlotte 2. Filming was confi ned mostly to weekends, with scenes to suit the changing seasons

1. Garrow Shand as Old Tom and Lyn Brooks as Charlotte 2. Filming was confi ned mostly to weekends, with scenes to suit the changing seasonsPeter is a Suffolk man himself, born in Bury St Edmunds, son of a stationmaster. He invited Ronnie to lunch, to talk as one Suffolk man to another about the possibility of translating Akenfield into a film.

Ronnie had his doubts, believing the book to be ‘unfilmable’, as he put it. But he was persuadable, and came up with a brief outline, centred on the funeral of a farmworker, Old Tom, whose life is recalled in a series of flashbacks.

The old man has never left the village where he was born, apart from fighting in the First World War. He constantly urged Young Tom, his grandson, not to stay on the land and endure the kind of suffering he had known. When Old Tom dies, his tied cottage is offered to Young Tom. He ponders his grandfather’s warning: should he stay or leave and find his fortune somewhere else?

There was no script, only Ronnie’s 18-page synopsis. There were to be no actors, only Suffolk people who would be given the briefest hints as to what any scene was about. With no script there were no words to learn; the words were their own. But who would these Suffolk people be?

An advertisement yielded several aspiring players. ‘All sorts of completely unsuitable people applied, saying they could do the accent, and all that kind of thing,’ says Ronnie. But some were suitable. One was Garrow Shand, a young agricultural contractor who they cast to play the parts of both Young Tom and his grandfather as a young man. ‘I can do ploughing, and it’ll be a laugh, won’t it?’ was Garrow’s thinking.

‘Sir Peter Hall’s searching for a wench for his film,’ was what Lyn Brooks heard. She was a driving instructor then. ‘Look at my hands,’ she says now, ‘big, working hands. That’s what got me the part.’

The wench that she became was Charlotte, maid to an Edwardian household, courted by Old Tom, and married off the harvest field. Ronnie Blythe, in curly-brimmed bowler and dog collar appears as the vicar. On the wedding night Tom is so tired that he falls asleep, leaving Charlotte to put her pretty nightdress away for another day.

There was no need to advertise for Young Tom’s mother. The right person lived almost on Ronnie’s doorstep. He took Peter Hall to see her at the flower show in the village hall.

‘And there she was, a very attractive woman, kind of rosy-faced,’ says Ronnie. Her name was Peggy Cole. Peter looked and listened, and said, ‘She’s the one.’

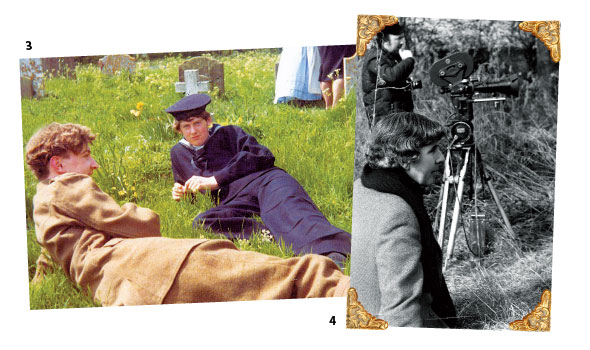

3. Filming was confi ned mostly to weekends, with scenes to suit the changing seasons 4. Ronnie Blythe (front) and Peter Hall (back) on location. Hall asked Blythe to be on the set as another pair of eyes and ears

3. Filming was confi ned mostly to weekends, with scenes to suit the changing seasons 4. Ronnie Blythe (front) and Peter Hall (back) on location. Hall asked Blythe to be on the set as another pair of eyes and earsIn church on Sunday, Ronnie told her. At fi rst she thought they wanted her to make tea.

On Valentine’s Day, 1973, Peggy and Garrow sat either side of a table. Peter asked them to row with each other, as mother and son. ‘I thought this was a rum do,’ says Peggy, ‘but I’ve got two sons, you see, so it wasn’t hard!’

Filming began in March, and almost straight away it had to stop again. In Peter Hall’s words, ‘Akenfield was amateur film-making in the proper sense of the word. We all did it for love…’

But the unions didn’t see it that way. Equity, the actors’ trade union, was seriously troubled and ‘blacked’ it, a stance that was vigorously challenged by actress Peggy Ashcroft who declared that this attitude would have stifled such films as Bicycle Thieves, an Italian post-war classic famous for its use of non-professional players. Equity retreated.

The professional technicians agreed to work on a co-operative basis, receiving no money until the film’s completion. They also agreed to operate as part of a smaller crew than normal. But nobody told their union, the Association of Cinematograph Television And Allied Technicians, about this voluntary departure from the rule book. The fi lm was blacked, but eventually a deal was done and the brethren were pacified. Work started again.

Bob Allen was the sound recordist, a New Zealander with a good deal of experience in feature-film work, and in documentaries, which was handy for the entirely location-based Akenfield. Loving East Anglia, he leapt at the invitation to work on it, to listen like Peter Hall for the music of Suffolk accents and record them crisply.

‘I would be thinking that qualitywise it’s okay. I mean I can hear all the words, but I can’t understand what they’re saying.’

Many of the amateur cast needed to earn their livings, so filming was confined mostly to weekends and extended over nearly a year, with scenes to suit the changing seasons. Working with non-professionals the producers depended absolutely on their goodwill. Would it last once the novelty had worn off? Ronnie Blythe says they hardly dared think about it.

‘You know what people are. They sometimes say, “Bugger that, I’m not coming any more.” But nobody did.’

One of the most memorable sequences involves Grandfather Tom as a young ploughman working with horses, shot on a bitter day in early March, with hoar frost and fog. Garrow was muffled up in clothes borrowed from a scarecrow, with a sack around his shoulders for more warmth.

‘That’s what it was like, wasn’t it?’ he says. ‘I can remember old boys on the farm saying what they used to do and how they worked in all weathers and that was it. They were old, weren’t they, when they were sort of 50.’

With Ivan Strasburg’s ravishing photography and Michael Tippett’s radiant music, Akenfi eld was chosen to open the London Film Festival on 18 November 1974. The Evening Standard’s film critic, Alexander Walker, had seen a rough cut.

‘It is without doubt not only Hall’s best work,’ he wrote, ‘but one of the best films, and certainly the most unusual, made in and about England.’

In spite of its critical success, for various reasons Akenfield has been in partial hibernation, seen only now and then, but always admired and loved. It launched none of its players into a glittering film career. Peggy Cole has done countless talks about the film, here and in America. Garrow went back to agricultural contracting. Lyn Brooks works in farm administration. Everybody involved was enriched by the experience, but fi nancially nobody seems to have made much from it. Ronnie Blythe reckons he received about £500.

‘Got lots of books sold, though.’